What to Do When One Lift Lags Behind The Others

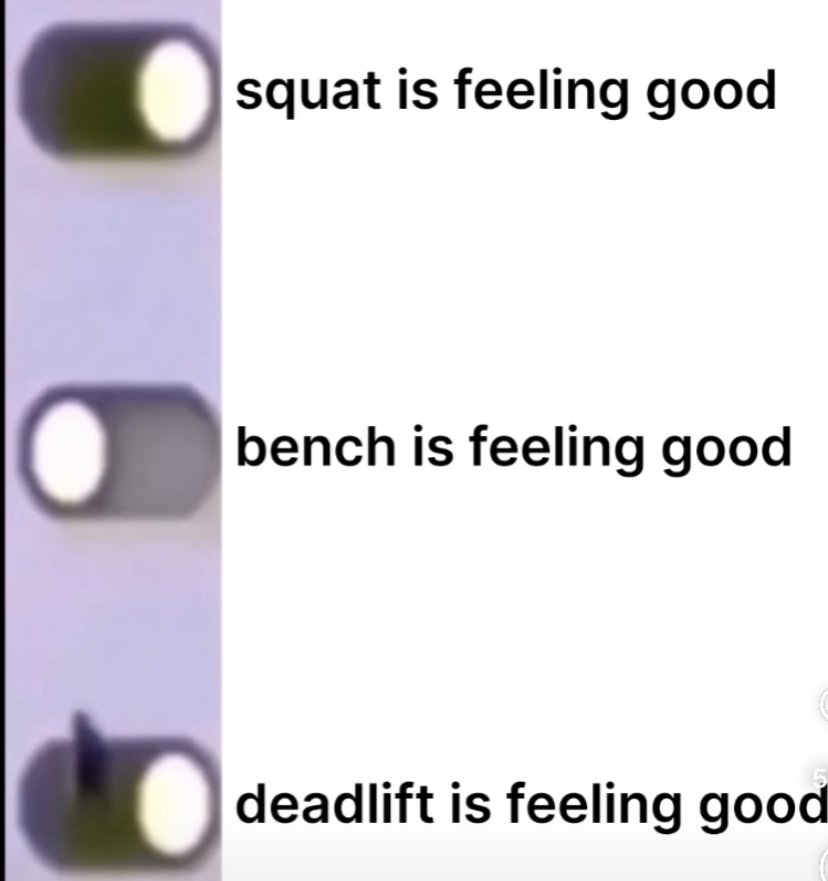

This recent meme has been circulating on Instagram, with “on/off” batteries listed next to the Big 3. The joke is that when squat goes up, bench & deadlift decrease, and when bench goes up, squat & deadlift decrease, and so on. The experience is shared among many Powerlifters. In a sport that, in many ways, is pretty simplistic and straightforward, it’s seemingly easy to assess whether we’re progressing. It’s objective. The bar doesn’t lie to you. And past the newbie stage, consistently making progress with all simultaneously- can feel impossible.

In some respects, it is.

Indeed, your other lifts shouldn’t necessarily decrease when you’ve made friends with one of them. If that's your consistent experience, it's worth looking into. But they may stagnate for a couple of training blocks, and that’s normal. The expectation that all three of your lifts will trend upward for months and years to come, without any deviation, is a fantasy world- specifically if you’re a raw, natural lifter. Plateaus happen, and we can’t always control (or know what are) the factors that cause them. Those phases can become the most enriching and developmental for you as an athlete.

If you were always adding weight to the bar without any challenge, how would you build:

Fortitude?

Discipline?

Meaning behind your lifts?

On a more concrete basis, how would you know to:

Experiment with your technique, making it more efficient?

Find out that you could handle more volume- and that incorporating more would make you stronger?

That your setup/approach could be improved upon, all in the process of making you better?

We have our greatest breakthroughs and lessons as Powerlifters during the hard times because they force us to look inward & explore how to continue expounding. And that is the sole goal of our sport.

Moreover, sometimes one lift needs more work than the others. If you’re a self-proclaimed Deadlift specialist, what are the negatives to putting it on the back burner for a bit- to build your squat? Maybe it was what needed to happen- so you could focus your energy on what requires more from you.

Plateaus can be a positive, more so than unwavering linear progression would be. Plateaus deepen tenacity, rebuild lifts, and evoke beneficial change. We need to reframe how we discuss and view these periods.

Yet, a plateau without introspection, awareness, or alterations can become a prolonged wall, harder and harder to break as you get further into your career. Continually stalled progress is indicative of something worth questioning. The bottom line is that when these discouraging moments occur, how you respond is crucial. The only way to derive benefit from the hindrance is to control your answer to it. So, long-winded introduction aside, what are your next steps when you realize you’ve got a lift that doesn’t want to budge?

Assess recovery habits & consistency.

This is the first question I ask every lifter who feels dissatisfied with their rate of progression.

First and foremost, consistency. If you’re not showing up to your sessions (3x/week at a minimum) with at least 90%-95% consistency, you have no business looking into literally anything else. Your program isn’t the problem- it’s how you’re following it.

Discuss the topic with your coach to determine how you could make it into the gym more often.

Beyond that, it’s food/sleep/stress levels/drinking/etc.

Are you eating enough? Around training sessions?

Carbs, protein, fats, fruits, veggies, all the essentials?

Are you sleeping 7-9 hours per night, most nights?

How’s your brain doing? Do you have tools to manage your emotions, preserve space for yourself, and recover from life? Are you feeling overwhelmed and excessively “out of it” in this phase of life?

How often are you drinking/partying?

Are you doing other movements on days off? Excessive cardio? Or, on the opposite side, nothing at all?

Many of us have blindspots and shortcomings here, which is not something to be ashamed or guilty of. It’s extremely common, and sometimes we aren’t even aware of it ourselves. But before you complain about your lack of progress and ask for some crazy variation, look inward and assess your life. Set goals to improve your habits- (if applicable) and have continual conversations with your coach about those goals.

2. Identify & modify technical changes.

Often, the next step I look at when a lifter is not making the progress they should (assuming a consistent training level) is their technique. The purpose of a technical standard in Powerlifting is efficiency. You want to orient your body in a way to move the most amount of weight possible. And the technique you begin with in Powerlifting- is often different from what you end with.

It is a sport of continually collecting data and assessing tweaks to improve you. Of course, there’s no reason to change technique to change it- if it’s serving you. But, if your progress seems particularly slow, your current technique may not be fully developed.

Before you look at changing your setup & starting position, take a look at your execution.

Are you maintaining tension well during the lift?

Do you notice inconsistencies from rep to rep?

Does your positioning drastically change through the concentric (upward) portion?

Are your hips rising out of the hole, back caving in, elbows flaring out, etc?

Watch videos of yourself lifting, and listen to your coach’s feedback. Any loss in tension or positioning is an inefficiency, which could cost you pounds across your lifts- so addressing these should increase your performance.

If you’re doing a decent job of maintaining the above (remember that the “perfect” technique is an unattainable facade), you could try changing the mechanics of the lift itself. This could include:

Squat:

stance width (wider may be stronger- unless someone is starting from an excessively wide position. About hip width works best for some people), toe out

grip width (a wider grip can help increase back tension)

lifting in shoes/flats (for some, squat shoes will be stronger- making the lift more quad dominant, and for others, flats will be stronger- more posterior-chain dominant),

Bar position (Low Bar will be heavier for the vast majority of people, and optimizing bar placement is a factor, too),

Bench:

Arch (Many people can get more arch than they are currently placing themselves in. Get as high on your traps as possible, and compress your body as much as possible).

Leg Drive (Turning the feet outward/heels in can help prevent the butt from coming up. Practice leg drive without any weight on the bar; if you struggle to get it down).

Expanding the Rib Cage: Often missed on the bench press. Think about reaching your chest up to the bar/”creating a pregnant belly” to decrease the distance between yourself and the weight.

Grip width: For many athletes, a moderate grip (about pinky fingers on the knurling marks) works well. For some, a wider grip may feel easier.

Deadlift:

Stance: Whether you choose Sumo or Conventional can change throughout your career. You may be married to one position now, but later, feel that the opposite is stronger for you. Consider experimenting.

Foot position: Taking your chosen stance, try either a) moving your feet out wider (Sumo) or b) closer (conventional), as examples. This change may increase efficiency.

Hip position: You might start the lift with your hips too high/low- or with the bar too far away from your body.

Look for ways to alter your technique to move more weight, making the lift more efficient. Of course, I can’t guarantee that a wider grip/more toe out or whatever will increase your Big Three immediately. Everyone's bodies are built differently- and their movements will change- as a result. There will always be outliers, and the “good technique” continuum is broad- requiring experimentation.

3. Change frequency/volume.

Look at your training program and assess how it’s supporting you.

Ask questions such as, are you training with the most volume you could recover from? How often are you training each lift?

One of the simplest methods to increase a specific lift is to incorporate a “specialization phase,” where you emphasize it more than the others. Obviously, we’d like to prioritize all three, but this isn’t always realistic. During a phase like this, you up the frequency of a given lift. If it’s a bench specialization phase, that could be training bench 3-4x/week instead of just 2. For squats, that could be 2-3x/week.

Note that super high-frequency training (i.e. “Squat Every Day” is an advanced method, but for beginner/intermediate lifters looking to progress further, simply adding one more training day for the given lift can be adequate).

You may also look at incorporating more volume. If you never go beyond 4x4s or even 5x5s, you’ve probably got some gaps in your training. You may be able to handle more than you think, and the work capacity, hypertrophy, and technical proficiency built with higher-volume training can do wonders for your 1RMs. Dedicate a few blocks to building up your workload, and once you taper it down, you’ll be surprised at the results.

On the contrary, maybe your volume/frequency/intensity is too high. This case is rarer when following structured programs- everything is usually pretty controlled, but it’s possible. You’ll know whether this is your case based on biofeedback factors- pain levels post-training, fatigue, and strength performance. If all of these are decreasing consistently, consider pulling back a bit.

Programming variables are one factor going into plateaus- and often the first place many jump to; possibly ignoring other key components. But regardless, it’s an important assessment, and you may find your answer lies there.

4. Target potential weaknesses.

A possibility for a lift plateau is that you may have a weakness that needs addressing. Note that this should be a question further down the list, applying more so to intermediate/advanced lifters.

Generally, technique is a more common shortcoming: hips rising out of the hole in a squat, rounded backs causing inefficient lockouts, etc. Yet, you can supplement technical weaknesses with strategic exercise selection. Programming lifts that inherently help address bar path issues, challenge your ability to maintain tension, improve your bodily awareness, etc., can help you alter them in your primary lifts. If you have identified room for technical improvement, consider adding variations that help target that. For example, maybe you’re struggling with compromised positioning off the floor in your deadlift (a very common one). Helpful variations include Paused reps, Slow Eccentrics, Boris deadlifts, etc. These movements all help improve your time under tension & bodily awareness during the set- which carries over to your main lifts.

The other possible weakness here is a physical/muscular one. Maybe your triceps are genuinely weaker than your shoulders, to the level of impacting your bench. Or your quads are underdeveloped compared to your hips/glutes, causing technical faults in your squat and decreasing your strength. These experiences are far from common among especially newer/intermediate lifters- but might be worth considering if you’ve exhausted every other issue/have reason to believe so.

In this case, you’ll want to choose variations further targeting those regions & adding extra accessory volume. For example, if you’ve got weak quads, you may add Front Squats/High Bars/SSBs, etc., as well as more leg extensions/goblet squats/split squats/etc. Specializing in these muscle groups, for a phase or two, would theoretically bring up your main lifts.

Sometimes, when a lift is lagging, it may be due to individual deficiencies within the movement itself, and closing in your programming around that factor can help break your plateau.

5. Acknowledge that it’s part of the process.

Finally, we must reinstate the inevitable.

Plateaus will happen.

As mentioned above, your lifts will never increase together forever, without any deviation. That stage exists for about six months and is called “Newbie Gains,” but most of us are in this sport for longer than that. As an intermediate, you’ll still make decently timed progress for a while, with some back-and-forth here and there, and as an advanced lifter, you’ll be scraping by for 5-10 lbs on your lifts. It’s how it goes. Once you get better, it gets harder. I like to reframe this as; the increased effort and difficulty enhance the meaning of your lifts. Sure, it’s fun to add weight to the bar every session, but when that’s your expectation- you don’t build as much satisfaction in your accomplishments. It just happens- and it’s fun, but there’s not as much beneath the surface.

Once you have to really work, grind, cry, doubt, and question around your lifts- they start to become more significant. What you put into them- and eventually get out of them, parallels your life and character growth to a greater degree, which keeps you hungry and invested going forward.

And as briefly touched on in the introduction, the plateaus are where we:

Learn about ourselves,

Are forced to truly evolve,

May have to approach things differently to evoke a new outcome.

These developments take significant introspection and willingness to improve. During this time, you build yourself as an individual in this sport, creating success for your future, not just right now.

Of course, we want our lifts to go up. If we didn’t care about them- it defeats the entire purpose of this pursuit in the first place. But we must remain patient and committed during the plateaus.

And let’s clarify that:

If your lifts don’t go up for anywhere from a week to three months, you’re not necessarily “in a plateau.” We don’t test our lifts that often anyways, so it’s hard to know whether they've improved.

If you’re not adding weight to the bar every week, that doesn’t mean you’ve plateaued either. It’s a delusional assumption that you can increase each lift every week without fail.

If you’re not adding 30-50 lbs each testing phase- you’re not in a plateau. PRs are PRs, and as you get stronger, you take what you can get.

I would define a plateau as a lift remaining the same (or decreasing) throughout a 5-12-month period (depending on factors such as training age). If, with consistent training for multiple months, your lifts haven’t budged- without any immediate explanation, that can be considered a plateau.

All lifters will likely experience this at some point in their career. Does it suck? Yes, as individuals who internalize our strength accomplishments and invest a lot into them, feeling as if your efforts have gotten you nowhere is devastating. You can recognize that. But, ruminating in those emotions, continuing to complain about it? That won’t help. There’s an explanation, even if you can’t see it now. You’re not a "special butterfly" to whom the general training principles don’t apply.

First, look at your life and habits, then assess your technique and programming. With another eye by your side, I guarantee you’ll find something.

Use this phase as an education period. Plateaus provide an opportunity- to search for answers and discover what you need to keep growing. It’s a valuable place to be if you view it that way. And once you break through it, a) it’ll mean even more to you, you’ll find relief and comfort in that win, and b) you’ll know more about yourself in future training phases, better equipped to handle whatever may arise.

-

Plateaus can be dreadful and frustrating as hell. None of us ever want to feel we aren’t progressing- or that our hard work went to waste. And yet, it’s a necessary and inevitable part of the training process- at some point. These periods can be our greatest moments of growth and learning, and we must work to redefine our perspectives in this way. Plateaus inspire us to search for answers, finding what we can do better. Maybe you’re not taking care of yourself outside of your sessions- and need to improve your life habits. Or, your technique leaves a lot to be desired, holding your progress back. Possibly, you can alter your programming- in a way to get that momentum going. Embark on an objective assessment once you’ve identified a true plateau is occurring, and I bet you’ll find a way to get yourself out of it.